Business

New report warns falling prices could squeeze Missouri farmers

[ad_1]

U.S. farm income is falling from record highs as low commodity prices, trade headwinds and higher costs squeeze profits, according to a new report from the University of Missouri.The 2024 U.S. Agricultural Market Outlook report released Tuesday by the Food & Agricultural Policy Research Institute, also known as FAPRI, is a 10-year projection of the agriculture economy. It examines production trends and pricing for commodity and specialty crops and livestock and discusses issues like interest rates, consumer prices and biofuel production that impact on farming as a whole.For producers, the news isn’t especially welcome.“We got lower commodity prices kind of across the board, except for cattle,” said Pat Westhoff, the agricultural economics professor who serves as the institute’s director.The annual report is eagerly anticipated in the agriculture industry and its findings have extra significance this year as Congress tries to pass a farm bill renewing producer support and food distribution programs.Net farm income nationally is expected to be about $118.2 billion this year, down from a record of about $162 billion in 2022.Westhoff said he briefed Congressional staff on the report Tuesday and the reaction was a classic glass half-empty, glass half-full split. Some saw the large decline in farm income as a problem, while others noted that income is expected to remain above the average from 2015 to 2019.“People were using the same numbers and making the opposite arguments,” Westhoff said.Missouri is second only to Texas in the number of farms, with 87,887 farms that sold $14.7 billion in agricultural products in 2022, up from $10.5 billion in 2017 according to the Census of Agriculture. Missouri farms also received nearly $1 billion in government payments or other income.With farm production expenses of $10.7 billion, Missouri farms had net cash income of $5 billion.The 5,596 largest Missouri farms, with sales of $500,000 or more, sold more than $11.6 billion of products in 2022. The 67,400 Missouri farms with sales of less than $50,000 sold $685 million agricultural products.Prices for grain and oil crops have fallen dramatically in the past year. Missouri farmers were receiving $14.90 a bushel for soybeans in January 2023, and $6.94 a bushel for corn. According to the monthly agricultural prices report from the National Agricultural Statistics Service, the price received for soybeans in January was $12.90 a bushel and for corn it was $4.79.The issues facing farmers nationally, Westhoff said, are true in Missouri, where corn, soybeans and wheat are the major cash crops.The FAPRI report projects the decline in commodity grain prices will slow, but continue.Missouri farmers get a slightly better price than the national average for corn and soybeans because of proximity to large rivers and industries such as ethanol and biodiesel that buy commodities locally, Westhoff said.“Where you have crushing facilities for soybeans matters tremendously,” Westhoff said. “Where you have ethanol plants matters as well.”Missouri produced 264.9 million bushels of soybeans in 2023. A decline of $2 per bushel means the farmers producing those beans received more than $500 million less than they did for the same commodity the previous year.The sharp decline in market prices for soybeans hasn’t been accompanied by a similar decline in prices for fertilizer, fuel and other supplies, said Casey Wasser, chief operating officer of Missouri Soybeans, the industry lobbying association.“The input prices have not come down at all with the other prices,” Wasser said. “So that’s where that net farm income is going to hit producers pretty tight.”Missouri has the nation’s sixth largest cattle herd. It also is home to the sixth largest number of hogs, and its farmers sold the seventh largest number of chickens for meat consumption and had the nation’s 12th largest flock of laying hens.But Missouri is losing farmers – and farmland – faster than the national average.The number of farms declined 7.8% since the 2017 farm census while nationally the number fell 6.9%. Nationally, 2.2% of farmland was converted to other uses between the surveys, while in Missouri the acreage in farming declined 2.7%.The smallest producers are being squeezed the tightest, said Tim Gibbons of the Missouri Rural Crisis Center. In a telephone interview after he spent a day lobbying in Washington for changes in national farm programs, Gibbons said the issues facing farmers go well beyond commodity prices and interest rates.Control of agriculture continues to be concentrated in large corporations, he said. Farm programs are designed to support cheap commodities and large producers, he said.“What I’m hearing on the Hill is a joke relative to the situation that is farming in Missouri and in the United States right now,” Gibbons said.Corporate-backed buyers are outbidding local residents for farmland and the concentration in meatpacking means producers become dependent on contracts that can be canceled when profits narrow. The decision by Tyson Foods to close a plant in Perry, Iowa, that employs 1,300 people will have a ripple effect on the farmers who raise hogs under contract, Gibbons said.Missouri has lost more than 1,000 cattle producers a year over the past 25 years, a trend that accelerated to about 2,000 per year in the past five years, according to the farm census. The number of farms producing hogs has declined from 12,133 in 1992 to 2,184 in 2022.“The policies that have been in recent past farm bills have been written by and for these multinational corporations and lobbyists that lobby for them,” Gibbons said. “We need a very different vision and a farm bill.”The only area where prices are increasing in the past year are for cattle. That’s because the national herd is at its lowest number since the 1960s, in large part due to pastureland drying up because of droughts starting in 2020.Short supplies are pushing prices up.“It’s causing liquidation and we’re not seeing rebuilding right now,” Gibbons said. “That connects with interest rates as well.”Higher interest rates in the United States, which increase costs for farmers as they borrow to finance annual operations or add land and equipment, put farmers at a disadvantage internationally by making the dollar worth more in exchange, Westhoff said.One indicator of the impact is that the U.S. has become a net importer of food and agricultural products, reversing decades of a surplus in the balance of farm trade.“We are importing lots of value-added products that might otherwise be produced here and of course that has spillover effects,” Westhoff said.The FAPRI report section on government aid to farmers notes that the cost of the two main programs intended to shore up prices – agricultural risk coverage, or ARC, and price loss coverage, or PLC fell below $1 billion because of recent high commodity prices.At the same time, crop insurance payments in 2023 totaled $9.3 billion.“We need to figure out a system of farmer-owned grain reserves and price floors and price ceilings to stop the volatility of the market, and keep that price floor at the cost of production,” Gibbons said.Missouri Soybean is pushing for changes in federal farm support programs to reset the protected prices at a higher level, Wasser said. Prices on beans could fall another $2 per bushel and Missouri farmers wouldn’t qualify for payments to make up any of the difference, he said.“We’re still not even close to a safety net, with inputs and $11 beans it’s tough for any farmer no matter what your size or your leverage to be making any profit on that,” Wasser said..FAPRI’s job is to provide information, not advise on policy decisions, Westhoff said.The difficulty of getting changes to the programs is cost, he said.Some “would like to do some changes that would improve the safety net from the perspective of producers but those changes all cost money,” he said. “And unless you’re going to reduce that spending or reduce spending on conservation programs, there’s not any obvious way to put those pieces together.”The decline in commodity prices should ease inflation in food costs and even reverse some recent increases, such as for eggs and pork, Westhoff said. Food purchased for consumption at home should not increase any faster than inflation generally, the report indicates.But consumers shouldn’t expect everything in the supermarket to get cheaper, he said.“For the most part, the share of those commodity prices that affect consumer food prices is pretty small,” Westhoff said. “Therefore even a significant decline in the farm level price doesn’t translate to any decline, or not a very big decline, in grocery store prices.”This story was originally published in The Missouri Independent, part of the States Newsroom.

[ad_2]

Source link

Business

Laclede’s Landing is moving from nightlife hub to neighborhood

[ad_1]

Laclede’s Landing has cycled through many identities throughout the history of St. Louis. Now, some people involved with its redevelopment in recent years hope the landing’s next one will be as a residential neighborhood.The small district tucked directly north of the Gateway Arch National Park has quietly undergone a massive redevelopment with more than $75 million pouring into the rehabilitation of many of the historic buildings at the landing.“We are starting to feel that momentum, especially in the last really 60 days. Things have drastically changed around here,” said Ryan Koppy, broker and owner of Trading Post Properties and the director of commercial property for Advantes Group.Advantes alone shouldered the rehabilitation of six of the historic buildings, which now sport a mix of apartments and retail or office space, he said. Four of those buildings are completed, and of the 119 apartments available, about 90% are filled, Koppy said.“It just shows you what kind of demand we do have for the area,” he said. “We’re separated from downtown a little bit, and for the tenants, their local park where they’re walking their dogs, it’s a national park.”

Sophie Proe

/

St. Louis Public RadioInterior of the Peper Lofts at Laclede’s Landing on Aug. 16

Another 40 apartments are set to come online next year along with some retail space, Koppy said. He added he’s noticed a wide range of people who are considering and moving into the newly refinished apartments.“It’s very mixed, surprisingly,” Koppy said. “We have a lot of young professionals, maybe on their second job out of [university], we have some empty nesters too.”Part of the newfound momentum comes from a new market, the Cobblestone, and coffee shop, Brew Tulum, opening recently and bringing more foot traffic to the area, said Brandyn Jones, executive director of the Laclede Landing Neighborhood Association. She added that more apartments are set to come online within the next few months.“We have a great riverfront area here and so there are plans in the works to activate those spaces, bring people in,” she said.That could be more daytime events, like a farmers market, music festivals (one of which is happening this weekend) or just bringing in food trucks to Katherine Ward Burg Garden, Jones said. It’s a departure from the identity the district held a few decades ago as a hub for nightlife and entertainment.“That’s part of what connects so many people to Laclede’s Landing,” Jones said. “It’s important to tell the story of where we’re evolving. It won’t be what it was in the same exact way, but it will still be fun, and it can be fun early morning, midday or late night.”It’s a view shared by Koppy.“It’s grown up, it’s a bit mature,” he said. “We’re not going to have 3 a.m. bars here anymore because we have residents here.”Koppy added that Advantes is joined by other developers working to rehabilitate buildings in the district.“We all work in unison,” he said. “If I get a call and [a client is] asking for something and maybe the square foot doesn’t really match up with what I have available, but I know it matches up over there, they’re getting a very warm welcome and introduction.”

Sophie Proe

/

St. Louis Public RadioRyan Koppy looks out the window of Brew Tulum Specialty Coffee Experience on Aug. 16 at the Cobblestone on Laclede’s Landing in downtown St. Louis.

This push toward making Laclede’s Landing a residential neighborhood also comes alongside broader conversations about the future of downtown St. Louis more generally as it looks to move away from a dependence on office space. While the city as a whole continues to lose population, downtown added about 1,700 people between 2010 and 2020, according to U.S. Census data.“It’s been wonderful timing to have all that going on, that stress that you’re not just in downtown to work has been critical to part of this rejuvenation and energy down here,” Jones said. “Sometimes people forget Laclede’s Landing is part of downtown, really the original downtown.”And success in the small district could spread beyond its small confines and potentially serve as a model for success, Koppy added.“My idea is, if we could get all the great things of St. Louis coming in through here, we can eventually spread that,” he said. “We understand we can’t change the whole world, but we’ll just make the effort to try and change the world around us.”

[ad_2]

Source link

Business

St. Louis barbecue festival Q in the Lou canceled

[ad_1]

The largest barbecue competition and tasting festival in St. Louis, Q in the Lou, has been canceled. The event was planned for Sept. 6-8, but organizers decided to cancel it due to poor ticket sales and insufficient corporate sponsorship.The traveling festival had low attendance in Denver last week, said Sean Hadley, a festival organizer.“We made the tough decision to cancel Q in the Lou,” said Hadley. “We’re seeing a lack of support … it’s just not there.”The traveling event first came to St. Louis in 2015 and drew hundreds of people to downtown St. Louis for barbecue, live music and a “major party.”“It shut down out of the blue … I’ve gone every year,” said Scott Thomas, local chef and food blogger. “It’s brilliant. You could take a tour of some really amazing barbecue restaurants and competition barbecue guys all in one place.”In a late July news conference, city officials touted Q in the Lou as a significant tourism draw and a boost for downtown revitalization.“Bringing a signature national festival back to downtown St. Louis … is making us stronger,” Greater St. Louis Inc. CEO Jason Hall said then.Less than a month later, ticket holders from every festival stop learned they’d be refunded. On Monday, organizers privatized the Q in the Lou website and deleted its social media accounts.Conner Kerrigan, a spokesperson for Mayor Tishaura Jones’ office, said city officials are disappointed the festival won’t be back this year.“St. Louis knows how to throw a festival … bringing people together to celebrate our culture is one of the things we do best as a city,” Kerrigan said in a statement. “Should Q in the Lou try to come back next year or any year after that, they’ll have the support of the Mayor Jones administration.”

[ad_2]

Source link

Business

Alton’s Jacoby Arts Center likely to relocate permanently

[ad_1]

The Jacoby Arts Center, a staple of Alton for many in the Metro East community, will likely permanently move out of its downtown building at the end of September.Its departure and relocation from the historic building that the arts center has called home for the past 20 years has created a tense situation for not only the arts center’s supporters but also the local development company working to revitalize Alton’s downtown that owns the building.“It’s an unfortunate situation,” said Chad Brigham, the chief legal and administrative officer with AltonWorks, the real estate company owned by another prominent local attorney working to develop the town. “I wish there wasn’t misunderstanding and disappointment in the community. It’s difficult sometimes to clarify that.”When news of the likely departure spread in June via a letter from the Jacoby Arts Center to its supporters, an outcry on social media quickly followed. Some assumed it would be the end of the arts center.“There’s a lot of feelings right now that I think are more about the building itself than there are about the Jacoby Arts Center,” said Valerie Hoven, vice president and treasurer of the nonprofit arts center’s board.For supporters of the Jacoby, moving from the building and likely never returning will be a sad affair. Exactly what’s next for the arts center remains unclear. However, Jacoby board members believe this will not be the end of the organization. It will likely look different though.

Sophie Proe

/

St. Louis Public RadioThe Jacoby Arts Center earlier this month in downtown Alton

Sophie Proe

/

St. Louis Public RadioThe Alton-based Jacoby Arts Center features more than 75 St. Louis-area artists and their work.

The history of the buildingFirst dubbed the Madison County Arts Council, the nonprofit arts center renamed itself after the Jacoby family gave it the current building in 2004. AltonWorks founder John Simmons purchased the Jacoby Building in September 2018, according to property records from the county.Managing the large building, at 627 E. Broadway, became too expensive for the Jacoby Arts Center. In 2018, the organization approached Simmons to purchase it, said Dennis Scarborough, a past president of the board and a downtown business owner.“Of course, it sounded really, really good,” Scarborough said of Simmons’ purchase. “He took over the insurance, property taxes, all those kinds of things that were really, really getting into our budget, and he rented it to us at a fair price.”The two parties entered into a lease agreement initially for five years. Since then, Simmons has spent more than $1 million in upkeep, taxes, insurance and more on the building. The lease has been extended twice until the end of September this year.Over the six years, Jacoby paid $1,500 per month, which covered a portion of the utilities.“It’s been wonderfully generous of AltonWorks,” Hoven said.Because the building is aging and needs repairs, Brigham with AltonWorks and those connected to the arts center have long known the Jacoby Arts Center would need to relocate — at least temporarily.

Renovations on the Jacoby building will begin this fall. They’ll include modernizing the aging building, repairing the old elevator and putting in apartments on the second and third floors.

News of the likely departure and controversyRenovations will begin this fall. They’ll include modernizing the aging building, repairing the old elevator and putting in apartments on the second and third floors.In May, it became clear that a preliminary proposal for the arts center to return to the building after renovations finished in 2026 would not work for them, Hoven said.She estimates the first floor and basement of the Jacoby Arts Building span roughly 20,000 square feet.

Chad Brigham is a business and legal adviser for AltonWorks.

AltonWorks’ initial idea floated to the arts center would only provide 2,553 square feet, according to both Hoven and Brigham. While the board calculated the price for the new space to be at least triple the current payment, Brigham said there was never a specific price discussed.“No discussion in terms of actual rent price,” he said.AltonWorks didn’t make a specific rent offer because the organization doesn’t even know itself, Brigham said.In addition to cash from John Simmons, there will be loans, tax increment financing and state tax credits to cover the $20 million in building renovations. The entities financing the cost of renovations will also help determine the rent when the construction is complete, Brigham said.Regardless, the price required to return will be too much for the arts center to pay, Hoven said. Also, the organization would like to maintain the many programs it offers to the community — a rentable event space, a dark room and a clay studio, for example — in the future.“For us to really meet the needs of the community and be sustainable, we need a space where we can offer some of those programs — the artists’ shop, and other spaces that offer some kind of income as well — so that we can continue to give money back to the community,” she said.AltonWorks offered at least two other locations as possible alternatives from their vast stock of buildings along Broadway to house the arts center during the roughly 18 months of construction. Those alternatives came with similar deals requiring the Jacoby to cover only utilities, Brigham said.“We did put in a great deal of work behind the scenes in trying to find an interim solution,” Brigham said. “We wanted to find a place for them to go, where it was easy for them to continue programming, whether it’s 100% of it or some portion of it, that would work for them.”Initially, the arts center hoped to keep the basement during the renovations, Hoven said. When it became clear the preliminary offer to return was for much less space than the arts center anticipated, the letter to the community was sent.“The letter that came out was merely showing our surprise,” Hoven said. “Don’t misinterpret it as panic. Don’t misinterpret it as desperation.”

Sophie Proe

/

St. Louis Public RadioA smorgasbord of radios are displayed at the Jacoby Arts Center in Alton.

The commentary on social media was passionate. Some critics of AltonWorks said the organization has good intentions but hasn’t executed those plans. Others said Jacoby hasn’t planned well enough for the future.For Brigham and the AltonWorks team, some of the criticism has been disappointing.“I thought that there were some decent solutions. Were they perfect? No, but they were very, I thought, very good solutions,” he said. “And the fact that it has come to the point that it is right now is a bit hurtful.”AltonWorks remains committed to the arts, Brigham said. John Simmons remains one the largest donors of the Jacoby Arts Center, Hoven and Brigham said.“I don’t think there’s ever been a question of our support of that organization — of our affinity for that organization,” Brigham said. “While some of the events were unfortunate, some of them were encouraging. The entire community rallied around the Jacoby Arts Center. That’s a good thing. It’s a good thing to have a love for the arts like that in a downtown community.”Sara McGibany, the executive director of Alton Main Street, an organization aimed at preserving the town, said AltonWorks should be commended for its vision. In many ways, her organization and AltonWorks share a vision for a thriving downtown.Even though AltonWorks hosts public meetings, McGibany believes the current situation lacks true community engagement.“We really think that if AltonWorks can get past some of the communication hurdles — and harness the community’s passion and shift to more of a bottom-up decision-making process that centers on community input — then we can turn around the growing sentiment of distrust that’s happening now,” McGibany said.Scarborough, the past board president and downtown business owner, echoed the praise for Simmons and his support of the Jacoby Arts Center. With the Jacoby likely moving, the future looks bleak, though.“It’s a community arts center that does a lot of good work,” Scarborough said. “The community is going to suffer, and they’re going to be missed by the community if they’re not there.”

Eric Lee

/

St. Louis Public RadioShalanda Young, director of the federal Office of Management and Budget, talks to Illinois U.S. Rep. Nikki Budzinski, D-Springfield, during a tour of a construction project by AltonWorks last April in Alton. AltonWorks, who is building the LoveJoy Apartment Complex is receiving over $1 million in federal funding.

What does the future hold?AltonWorks will continue forging ahead with its ambitious plans to revitalize Alton. The organization hopes to conclude construction on the Wedge Innovation Center, which will have a restaurant, retail and co-working space, this fall. Lucas Row, a mix of apartments and retail space, is scheduled to be completed next spring.The remainder of the arts and innovation district, currently named after the Jacoby, will also move forward.“I believe in two years it’s going to be a much different place,” Brigham said of Alton. “It’s going to be thriving. It’s going to be new businesses, new tenants — and it’s going to be a nice proof of concept for what you can do in a small community like that.”The Jacoby board recently formed a strategic planning committee. Its task: figuring out what’s next for the arts center. The committee will reevaluate what space the Jacoby needs, what programs it wants to offer to the community and how they want to make that a reality.Keeping the arts center is essential for board members like Hoven. In her experience, it’s been a place where local aspiring artists get their start.“Art is one of the only ways to show your true authentic self,” Hoven said. “And there’s more people than I realized who do not get that opportunity every day.”The Jacoby will shut its doors to pack over the next month. Hoven said she’s optimistic the board will have concrete plans by the end of September when their lease officially ends.“Alton is such a fabulous and supportive community,” she said. “We still have lots of great options, so that the Jacoby Arts Center will continue to thrive in Alton and beyond.”

[ad_2]

Source link

-

Politics2 years ago

Politics2 years agoPrenzler ‘reconsidered’ campaign donors, accepts vendor funds

-

Board Bills1 year ago

2024-2025 Board Bill 80 — Prohibiting Street Takeovers

-

Board Bills3 years ago

Board Bills3 years ago2022-2023 Board Bill 168 — City’s Capital Fund

-

Business3 years ago

Business3 years agoFields Foods to open new grocery in Pagedale in March

-

Business3 years ago

Business3 years agoWe Live Here Auténtico! | The Hispanic Chamber | Community and Connection Central

-

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment2 years agoOK, That New Cardinals/Nelly City Connect Collab Is Kind of Great

-

Entertainment3 years ago

Entertainment3 years agoSt.Louis Man Sounds Just Like Whitley Hewsten, Plans on Performing At The Shayfitz Arena.

-

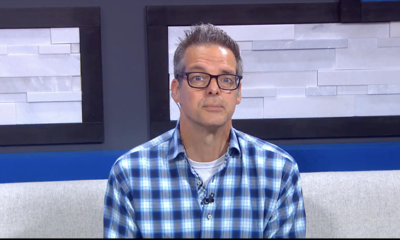

Local News2 years ago

Local News2 years agoFox 2 Reporter Tim Ezell Reveals He Has Parkinson’s Disease | St. Louis Metro News | St. Louis