Business

How the River Des Peres can become an asset for St. Louis

[ad_1]

Cities and towns across the Mississippi River basin, including St. Louis, have always needed to weather the environmental disasters associated with living along a river.The past few years have brought wild fluctuations between flooding and drought, bringing more stress to the communities nestled along the Mississippi’s 2,350 miles.In the past five years alone, they’ve seen springtime flooding, flash flooding, significant drought and low river levels, with opposite ends of this spectrum sometimes occurring in the same calendar year.“When these rivers have disasters, the disaster doesn’t stay in the river,” said Colin Wellenkamp, executive director of the Mississippi River Cities and Towns Initiative. “It damages a lot of businesses, homes, sidewalks and streets — even broadband conduit and all kinds of utilities, mains and water return systems.”The cost of those damages can run into the millions if not billions.One potential solution Wellenkamp encourages the 105 individual communities in his organization to consider is to work with, rather than against, the river.“Just about all of them have some sort of inlet into the Mississippi River that they’re built around,” he said. “Some of them are big, and some of them are really small. But all of them need attention.”It’s not a new idea, and many cities are already investing in nature-based solutions, such as removing pavement, building marshes and making room for the river to flow. Now, St. Louis is looking to learn from Missouri’s neighbors in Dubuque, Iowa, on what the city can do with its River Des Peres.

Eric Schmid

/

St. Louis Public Radio The River Des Peres between Gravois Avenue and Morganford Road on Dec. 3 in south St. Louis. The drainage ditch will fill up with water during heavy rains and prolonged flooding.

‘All-around gross’“It’s just an eyesore,” said Beatrice Chatfield, 15, who was walking along the River Des Peres pedestrian and bike greenway with her mom, Jen. “There’s trash and debris and muck in it. It’s just all-around gross.”It’s less of a river and more of a large concrete and stone-lined drainage channel that winds from the Mississippi through the urban landscape before disappearing beneath St. Louis’ largest park, Forest Park. It then reemerges farther west in the suburb of University City.“It’s basically the small version of the LA River, which is just a cesspool,” said Sam Rein, 29. “During the summer it smells — we don’t exactly like living next to it, but it’s a neat feat of engineering, that’s for sure.”It can also be dangerous, Wellenkamp said.“As the Mississippi River rises, the River Des Peres then begins to back up into people’s basements and yards and small businesses into the city,” he said.Some 300 homes flooded in University City alone when the St. Louis region was hit with record-breaking rainfall in July 2022. Wellenkamp argues St. Louis should look to other cities in the Mississippi River basin that have learned to work with water, instead of against it.

Brent Jones

/

St. Louis Public RadioThe River Des Peres flows out of its banks in June 2019 south of Interstate 55, near Gravois Creek and the Alabama Avenue bridge. The flooding then posted the highest reading on the gauge upstream at Morganford Road since at least 2002.

Dubuque’s hidden creekIn the late 1990s and early 2000s, Dubuque, Iowa, had a major flash flooding problem. Over the course of 12 years, the city of nearly 60,000 received six presidential disaster declarations for flooding and severe storms.Whenever heavy rains drenched the city, the water would rush down the bluff and overwhelm the stormwater infrastructure, said Dubuque Mayor Brad Cavanagh.Manhole covers erupted from the water pressure, turning streets into creeks and damaging thousands of properties.“Somewhere along the line about 100 years ago, somebody buried a natural creek and turned it into a storm sewer, and it wasn’t keeping up anymore,” Cavanagh said. “Many of the residents (in these neighborhoods) are low to moderate income and those least able to really recover from damage like this.”Around 2001, the city started looking for solutions.Dubuque faced a decision: expand the existing underground storm sewer or bring the Bee Branch Creek back into the daylight, expanding the floodplain and giving the water somewhere to go. The city opted for the latter option.

Provided

/

City of DubuqueA child fishes in the Bee Branch Creek in Dubuque, Iowa, in 2017. The creek has become a place where people can interface and learn about watersheds.

The city established a citizen advisory committee early on in the process, which played a central role in determining the eventual design for the restored Bee Branch Creek.Residents wanted more than a concrete drainage ditch, Cavanagh said. They wanted trails, grasses and greenery that wildlife and people could both enjoy, and, importantly, access to the water, he added.The Bee Branch Creek turned into a 20-year project that became much more than just an engineering solution for excess rainwater, Cavanagh said.“It is one of the most beautiful parks we have in the city, a place where people go and watch the ducks and the birds,” he said.Most important, it solved the city’s flash flooding issues, said Deron Muehring, Dubuque’s water and resource recovery center director, who before that role was an engineer involved with the Bee Branch restoration from start to finish.“2011 is the last presidential disaster declaration we had,” he said. “Now we haven’t had rains of that magnitude, but we have had significant rainstorms where we would have expected to have flooding and flood damage without these improvements.”

Provided

/

City of DubuqueAn aerial photo of the Bee Branch Creek in Dubuque, Iowa, in June 2018. The creek is the result of a project to convert a buried storm sewer into a linear park.

Learning from DubuqueOther river cities see Dubuque’s success and want to know how they can apply it to their own flooding challenges, Cavanagh said.“As mayor, I’ve talked about this project more than anything else,” he said. “People want to know: How did you do it? Why did you do it? What worked and what didn’t?”

Eric Schmid

/

St. Louis Public RadioDubuque Mayor Brad Cavanagh before giving testimony to the St. Louis Board of Aldermen Committee on Public Infrastructure and Utilities on Dec. 13.

Cavanagh covered those details during a presentation on the Bee Branch to St. Louis aldermen in December who were looking for ways to apply those lessons on the River Des Peres.Ward 1 Alderwoman Anne Schweitzer was inspired by the ideas.“I could wish all day long that things like this had started sooner,” Schweitzer said. “But we’re here now, and we have a responsibility. The length of time something will take always feels really long, but it takes longer if we don’t start.”Time isn’t the only constraint — so is money. The Bee Branch in Dubuque had a price tag near $250 million. The city found a mixture of state and federal grant dollars totaling $163 million related to disaster resiliency, the environment, transportation and recreation and tourism, leaving the city covering around $87 million, Cavanagh said.Midwest Climate Collaborative Director Heather Navarro said floodplain restoration projects like Bee Branch are worth the investment.“We have done a lot to pave over our floodplains and wetlands, but we know there’s a lot of inherent natural value in those,” she said. “Whether it is absorbing floodwaters, helping filter pollution, reducing soil erosion. When you start to add up those numbers, that really starts to change the economics. ”

Eric Schmid

/

St. Louis Public Radio Ward 1 Alderwoman Anne Schweitzer and Ward 9 Alderman Michael Browning listen to testimony about Iowa’s Bee Branch Creek during the St. Louis Board of Aldermen Public Infrastructure and Utilities Committee hearing on Dec. 13.

She adds that when cities improve existing infrastructure like roads, bridges and wastewater management, they should consider how to use nature-based solutions and reduce flood and other climate risks.“It’s not like we’re swapping out old infrastructure for new infrastructure,” Navarro said. For example, rain gardens can reduce pressure on wastewater drainage by absorbing excess water. Trees can reduce heat. “But we’re really taking a whole new approach to how this infrastructure is interrelated with other systems that we’re trying to provide for our community.”And there’s billions of dollars on the table from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and Inflation Reduction Act for communities to tackle projects that build resilience.The path forwardAs it stands, St. Louis is at the beginning of even considering what a project to bring more nature to the River Des Peres could even look like. The Army Corps of Engineers is also exploring projects, specifically in University City, that could help store rainwater during heavy rains.The next major step would be a feasibility study of the entire River Des Peres watershed, which encompasses a handful of municipalities, Schweitzer said.“There’s so many people who would need to be at the table to move something like this forward, which I don’t think is a bad thing,” she said.Navarro said if cities like St. Louis want to use natural infrastructure to reduce their flood risk, there’s no better time than now.“We know that climate change is impacting our communities,” she said. “We know that the way that we have been doing things in the past has in part contributed to where we are when it comes to the climate crisis.”Wellenkamp agrees.“Nature attracts business,” he said. “It stabilizes property value. It reduces crime. It creates resilience to disasters and extreme events. And it gives your place a better quality of life.”This story is a product of the Mississippi River Basin Ag & Water Desk, an independent reporting network based at the University of Missouri in partnership with Report for America, with major funding from the Walton Family Foundation. Sign up to republish stories like this one for free.

[ad_2]

Source link

Business

Laclede’s Landing is moving from nightlife hub to neighborhood

[ad_1]

Laclede’s Landing has cycled through many identities throughout the history of St. Louis. Now, some people involved with its redevelopment in recent years hope the landing’s next one will be as a residential neighborhood.The small district tucked directly north of the Gateway Arch National Park has quietly undergone a massive redevelopment with more than $75 million pouring into the rehabilitation of many of the historic buildings at the landing.“We are starting to feel that momentum, especially in the last really 60 days. Things have drastically changed around here,” said Ryan Koppy, broker and owner of Trading Post Properties and the director of commercial property for Advantes Group.Advantes alone shouldered the rehabilitation of six of the historic buildings, which now sport a mix of apartments and retail or office space, he said. Four of those buildings are completed, and of the 119 apartments available, about 90% are filled, Koppy said.“It just shows you what kind of demand we do have for the area,” he said. “We’re separated from downtown a little bit, and for the tenants, their local park where they’re walking their dogs, it’s a national park.”

Sophie Proe

/

St. Louis Public RadioInterior of the Peper Lofts at Laclede’s Landing on Aug. 16

Another 40 apartments are set to come online next year along with some retail space, Koppy said. He added he’s noticed a wide range of people who are considering and moving into the newly refinished apartments.“It’s very mixed, surprisingly,” Koppy said. “We have a lot of young professionals, maybe on their second job out of [university], we have some empty nesters too.”Part of the newfound momentum comes from a new market, the Cobblestone, and coffee shop, Brew Tulum, opening recently and bringing more foot traffic to the area, said Brandyn Jones, executive director of the Laclede Landing Neighborhood Association. She added that more apartments are set to come online within the next few months.“We have a great riverfront area here and so there are plans in the works to activate those spaces, bring people in,” she said.That could be more daytime events, like a farmers market, music festivals (one of which is happening this weekend) or just bringing in food trucks to Katherine Ward Burg Garden, Jones said. It’s a departure from the identity the district held a few decades ago as a hub for nightlife and entertainment.“That’s part of what connects so many people to Laclede’s Landing,” Jones said. “It’s important to tell the story of where we’re evolving. It won’t be what it was in the same exact way, but it will still be fun, and it can be fun early morning, midday or late night.”It’s a view shared by Koppy.“It’s grown up, it’s a bit mature,” he said. “We’re not going to have 3 a.m. bars here anymore because we have residents here.”Koppy added that Advantes is joined by other developers working to rehabilitate buildings in the district.“We all work in unison,” he said. “If I get a call and [a client is] asking for something and maybe the square foot doesn’t really match up with what I have available, but I know it matches up over there, they’re getting a very warm welcome and introduction.”

Sophie Proe

/

St. Louis Public RadioRyan Koppy looks out the window of Brew Tulum Specialty Coffee Experience on Aug. 16 at the Cobblestone on Laclede’s Landing in downtown St. Louis.

This push toward making Laclede’s Landing a residential neighborhood also comes alongside broader conversations about the future of downtown St. Louis more generally as it looks to move away from a dependence on office space. While the city as a whole continues to lose population, downtown added about 1,700 people between 2010 and 2020, according to U.S. Census data.“It’s been wonderful timing to have all that going on, that stress that you’re not just in downtown to work has been critical to part of this rejuvenation and energy down here,” Jones said. “Sometimes people forget Laclede’s Landing is part of downtown, really the original downtown.”And success in the small district could spread beyond its small confines and potentially serve as a model for success, Koppy added.“My idea is, if we could get all the great things of St. Louis coming in through here, we can eventually spread that,” he said. “We understand we can’t change the whole world, but we’ll just make the effort to try and change the world around us.”

[ad_2]

Source link

Business

St. Louis barbecue festival Q in the Lou canceled

[ad_1]

The largest barbecue competition and tasting festival in St. Louis, Q in the Lou, has been canceled. The event was planned for Sept. 6-8, but organizers decided to cancel it due to poor ticket sales and insufficient corporate sponsorship.The traveling festival had low attendance in Denver last week, said Sean Hadley, a festival organizer.“We made the tough decision to cancel Q in the Lou,” said Hadley. “We’re seeing a lack of support … it’s just not there.”The traveling event first came to St. Louis in 2015 and drew hundreds of people to downtown St. Louis for barbecue, live music and a “major party.”“It shut down out of the blue … I’ve gone every year,” said Scott Thomas, local chef and food blogger. “It’s brilliant. You could take a tour of some really amazing barbecue restaurants and competition barbecue guys all in one place.”In a late July news conference, city officials touted Q in the Lou as a significant tourism draw and a boost for downtown revitalization.“Bringing a signature national festival back to downtown St. Louis … is making us stronger,” Greater St. Louis Inc. CEO Jason Hall said then.Less than a month later, ticket holders from every festival stop learned they’d be refunded. On Monday, organizers privatized the Q in the Lou website and deleted its social media accounts.Conner Kerrigan, a spokesperson for Mayor Tishaura Jones’ office, said city officials are disappointed the festival won’t be back this year.“St. Louis knows how to throw a festival … bringing people together to celebrate our culture is one of the things we do best as a city,” Kerrigan said in a statement. “Should Q in the Lou try to come back next year or any year after that, they’ll have the support of the Mayor Jones administration.”

[ad_2]

Source link

Business

Alton’s Jacoby Arts Center likely to relocate permanently

[ad_1]

The Jacoby Arts Center, a staple of Alton for many in the Metro East community, will likely permanently move out of its downtown building at the end of September.Its departure and relocation from the historic building that the arts center has called home for the past 20 years has created a tense situation for not only the arts center’s supporters but also the local development company working to revitalize Alton’s downtown that owns the building.“It’s an unfortunate situation,” said Chad Brigham, the chief legal and administrative officer with AltonWorks, the real estate company owned by another prominent local attorney working to develop the town. “I wish there wasn’t misunderstanding and disappointment in the community. It’s difficult sometimes to clarify that.”When news of the likely departure spread in June via a letter from the Jacoby Arts Center to its supporters, an outcry on social media quickly followed. Some assumed it would be the end of the arts center.“There’s a lot of feelings right now that I think are more about the building itself than there are about the Jacoby Arts Center,” said Valerie Hoven, vice president and treasurer of the nonprofit arts center’s board.For supporters of the Jacoby, moving from the building and likely never returning will be a sad affair. Exactly what’s next for the arts center remains unclear. However, Jacoby board members believe this will not be the end of the organization. It will likely look different though.

Sophie Proe

/

St. Louis Public RadioThe Jacoby Arts Center earlier this month in downtown Alton

Sophie Proe

/

St. Louis Public RadioThe Alton-based Jacoby Arts Center features more than 75 St. Louis-area artists and their work.

The history of the buildingFirst dubbed the Madison County Arts Council, the nonprofit arts center renamed itself after the Jacoby family gave it the current building in 2004. AltonWorks founder John Simmons purchased the Jacoby Building in September 2018, according to property records from the county.Managing the large building, at 627 E. Broadway, became too expensive for the Jacoby Arts Center. In 2018, the organization approached Simmons to purchase it, said Dennis Scarborough, a past president of the board and a downtown business owner.“Of course, it sounded really, really good,” Scarborough said of Simmons’ purchase. “He took over the insurance, property taxes, all those kinds of things that were really, really getting into our budget, and he rented it to us at a fair price.”The two parties entered into a lease agreement initially for five years. Since then, Simmons has spent more than $1 million in upkeep, taxes, insurance and more on the building. The lease has been extended twice until the end of September this year.Over the six years, Jacoby paid $1,500 per month, which covered a portion of the utilities.“It’s been wonderfully generous of AltonWorks,” Hoven said.Because the building is aging and needs repairs, Brigham with AltonWorks and those connected to the arts center have long known the Jacoby Arts Center would need to relocate — at least temporarily.

Renovations on the Jacoby building will begin this fall. They’ll include modernizing the aging building, repairing the old elevator and putting in apartments on the second and third floors.

News of the likely departure and controversyRenovations will begin this fall. They’ll include modernizing the aging building, repairing the old elevator and putting in apartments on the second and third floors.In May, it became clear that a preliminary proposal for the arts center to return to the building after renovations finished in 2026 would not work for them, Hoven said.She estimates the first floor and basement of the Jacoby Arts Building span roughly 20,000 square feet.

Chad Brigham is a business and legal adviser for AltonWorks.

AltonWorks’ initial idea floated to the arts center would only provide 2,553 square feet, according to both Hoven and Brigham. While the board calculated the price for the new space to be at least triple the current payment, Brigham said there was never a specific price discussed.“No discussion in terms of actual rent price,” he said.AltonWorks didn’t make a specific rent offer because the organization doesn’t even know itself, Brigham said.In addition to cash from John Simmons, there will be loans, tax increment financing and state tax credits to cover the $20 million in building renovations. The entities financing the cost of renovations will also help determine the rent when the construction is complete, Brigham said.Regardless, the price required to return will be too much for the arts center to pay, Hoven said. Also, the organization would like to maintain the many programs it offers to the community — a rentable event space, a dark room and a clay studio, for example — in the future.“For us to really meet the needs of the community and be sustainable, we need a space where we can offer some of those programs — the artists’ shop, and other spaces that offer some kind of income as well — so that we can continue to give money back to the community,” she said.AltonWorks offered at least two other locations as possible alternatives from their vast stock of buildings along Broadway to house the arts center during the roughly 18 months of construction. Those alternatives came with similar deals requiring the Jacoby to cover only utilities, Brigham said.“We did put in a great deal of work behind the scenes in trying to find an interim solution,” Brigham said. “We wanted to find a place for them to go, where it was easy for them to continue programming, whether it’s 100% of it or some portion of it, that would work for them.”Initially, the arts center hoped to keep the basement during the renovations, Hoven said. When it became clear the preliminary offer to return was for much less space than the arts center anticipated, the letter to the community was sent.“The letter that came out was merely showing our surprise,” Hoven said. “Don’t misinterpret it as panic. Don’t misinterpret it as desperation.”

Sophie Proe

/

St. Louis Public RadioA smorgasbord of radios are displayed at the Jacoby Arts Center in Alton.

The commentary on social media was passionate. Some critics of AltonWorks said the organization has good intentions but hasn’t executed those plans. Others said Jacoby hasn’t planned well enough for the future.For Brigham and the AltonWorks team, some of the criticism has been disappointing.“I thought that there were some decent solutions. Were they perfect? No, but they were very, I thought, very good solutions,” he said. “And the fact that it has come to the point that it is right now is a bit hurtful.”AltonWorks remains committed to the arts, Brigham said. John Simmons remains one the largest donors of the Jacoby Arts Center, Hoven and Brigham said.“I don’t think there’s ever been a question of our support of that organization — of our affinity for that organization,” Brigham said. “While some of the events were unfortunate, some of them were encouraging. The entire community rallied around the Jacoby Arts Center. That’s a good thing. It’s a good thing to have a love for the arts like that in a downtown community.”Sara McGibany, the executive director of Alton Main Street, an organization aimed at preserving the town, said AltonWorks should be commended for its vision. In many ways, her organization and AltonWorks share a vision for a thriving downtown.Even though AltonWorks hosts public meetings, McGibany believes the current situation lacks true community engagement.“We really think that if AltonWorks can get past some of the communication hurdles — and harness the community’s passion and shift to more of a bottom-up decision-making process that centers on community input — then we can turn around the growing sentiment of distrust that’s happening now,” McGibany said.Scarborough, the past board president and downtown business owner, echoed the praise for Simmons and his support of the Jacoby Arts Center. With the Jacoby likely moving, the future looks bleak, though.“It’s a community arts center that does a lot of good work,” Scarborough said. “The community is going to suffer, and they’re going to be missed by the community if they’re not there.”

Eric Lee

/

St. Louis Public RadioShalanda Young, director of the federal Office of Management and Budget, talks to Illinois U.S. Rep. Nikki Budzinski, D-Springfield, during a tour of a construction project by AltonWorks last April in Alton. AltonWorks, who is building the LoveJoy Apartment Complex is receiving over $1 million in federal funding.

What does the future hold?AltonWorks will continue forging ahead with its ambitious plans to revitalize Alton. The organization hopes to conclude construction on the Wedge Innovation Center, which will have a restaurant, retail and co-working space, this fall. Lucas Row, a mix of apartments and retail space, is scheduled to be completed next spring.The remainder of the arts and innovation district, currently named after the Jacoby, will also move forward.“I believe in two years it’s going to be a much different place,” Brigham said of Alton. “It’s going to be thriving. It’s going to be new businesses, new tenants — and it’s going to be a nice proof of concept for what you can do in a small community like that.”The Jacoby board recently formed a strategic planning committee. Its task: figuring out what’s next for the arts center. The committee will reevaluate what space the Jacoby needs, what programs it wants to offer to the community and how they want to make that a reality.Keeping the arts center is essential for board members like Hoven. In her experience, it’s been a place where local aspiring artists get their start.“Art is one of the only ways to show your true authentic self,” Hoven said. “And there’s more people than I realized who do not get that opportunity every day.”The Jacoby will shut its doors to pack over the next month. Hoven said she’s optimistic the board will have concrete plans by the end of September when their lease officially ends.“Alton is such a fabulous and supportive community,” she said. “We still have lots of great options, so that the Jacoby Arts Center will continue to thrive in Alton and beyond.”

[ad_2]

Source link

-

Politics2 years ago

Politics2 years agoPrenzler ‘reconsidered’ campaign donors, accepts vendor funds

-

Board Bills2 years ago

2024-2025 Board Bill 80 — Prohibiting Street Takeovers

-

Board Bills3 years ago

Board Bills3 years ago2022-2023 Board Bill 168 — City’s Capital Fund

-

Business3 years ago

Business3 years agoFields Foods to open new grocery in Pagedale in March

-

Business3 years ago

Business3 years agoWe Live Here Auténtico! | The Hispanic Chamber | Community and Connection Central

-

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment2 years agoOK, That New Cardinals/Nelly City Connect Collab Is Kind of Great

-

Entertainment3 years ago

Entertainment3 years agoSt.Louis Man Sounds Just Like Whitley Hewsten, Plans on Performing At The Shayfitz Arena.

-

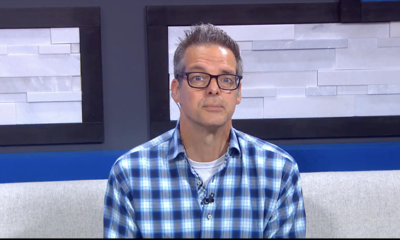

Local News3 years ago

Local News3 years agoFox 2 Reporter Tim Ezell Reveals He Has Parkinson’s Disease | St. Louis Metro News | St. Louis