Entertainment

Civil War Buffs Are Coming to St. Louis to Remember the Sultana Disaster

[ad_1]

For 25 years, Gene Salecker worked as a university police officer. There, Salecker met his wife, a professor, who inspired him to transition to the classroom, where he taught eighth grade for 12 years. Upon retiring in 2015, he became a full-time military historian, writing seven books in total on the Civil War and World War II. He has spent more than 30 years researching the Sultana Disaster and has become one of its leading authorities.

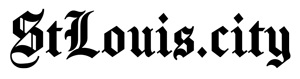

On April 27, 1865, the steamboat Sultana exploded on the icy cold Mississippi River, resulting in the greatest loss of life in a naval disaster in American history. The steamboat had been carrying 1,960 Union soldiers who’d been held as prisoners-of-war at two notorious Confederate prisons.

On April 26 and 27, descendants of victims and survivors, as well as history buffs, will gather in St. Louis for the annual Sultana Association reunion to honor and memorialize the Sultana Disaster. Salecker recently joined us to explain more about the disaster — and what keeps the story alive today.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Why has the Sultana’s explosion gone relatively overlooked by history?

I read all the Civil War books and nobody mentioned the Sultana. The reason that Sultana is so little known is it occurred at the same time that Abraham Lincoln was assassinated. In fact, the Sultana, which had a home base in St. Louis, set out from St. Louis on the eve on the morning of April 14, 1865, and went down river. It was at Cairo, Illinois, the next morning, April 15th, when word came through the telegraph that Lincoln had been assassinated in Washington. The captain of the Sultana, James Cass Mason, who also lived in St. Louis, knew that the South wouldn’t have gotten this information because the telegraph lines were all torn up. So he grabbed as many newspapers as you could get and started off downriver as the first steamboat to spread the word of Lincoln’s assassination to the south. He wanted to go down in history as the messenger of death, so to speak, and get himself a name.

The Sultana disaster happened on April 27, 1865, almost two weeks later. Well, all the newspapers are now reporting the search for John Wilkes Booth, who was shot on April 26. One day before the disaster there will be reporting on Lincoln’s funeral train traveling across the United States to all these different stops, and all the newspapers talking about that. All this crowded out the Sultana.

Senator John Covode from Pennsylvania traveled out to Memphis, Tennessee, where the Sultana had exploded, and he found out that the men on board were from Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Kentucky and Tennessee, all of what were called the Western states. After he reported this, the big newspapers in New York and Boston and Philadelphia just sort of said, ‘Oh, that’s the Western guys that died. We won’t worry about them.’ They had little blurbs here and there about the Sultana, but it would be on page four of a four-page newspaper all the way in the back.

click to enlarge COURTESY OF GENE SALECKER Gene Salecker was amazed that a tragedy as riveting as the Sultana’s explosion could largely slip out of the public consciousness.

How did you personally get into Sultana documentation? What makes you so dedicated?

I was just amazed that something like this could slip through the cracks of history. There was a survivor who worked with the Sultana Survivors Association, which was the actual survivors, and he collected their reminiscences. At 92, he published a book, Loss of the Sultana and Reminiscences of Survivors. It’s everybody’s personal accounts of what happened, 180 guys or something like that. When you read through it, what these guys went through, it just amazed me: Why did this fellow survive? And why did his friend or partner not survive? What did this guy do that was right and this other guy do that was wrong? It could have been just as simple as one fellow went to sleep with a blanket on and another person just lay down next to him. When the scalding water from the exploding boilers hit them, the blanket got soaking wet, but he survived, but the other guy got scalded. Some simple little thing like that. This happens at two o’clock in the morning on a dark river seven miles north of Memphis, and they started grabbing onto each other rather than jump from the side of the boat where there weren’t as many people. There were, I believe, 962 survivors, and how did they survive? That’s what got me.

This slip through history is something that occurs almost in the geographic center of the United States. And yet, we don’t know about it. We know about the Titanic. We know about the Lusitania, which are English ships. And yet here is an American vessel — all the greed and corruption that went with the overloading of it — and to have it happen and then to be swept into the back pages of history. That’s why I thought, no, we’ve got to work on this to get this so people know what’s going on.

Decades after the last Sultana Survivors Association meeting, in 1931, the association was revived as the Association of Sultana Descendants and Friends. What led to that happening in 1987?

Norman Shaw lives in Knoxville, Tennessee, and was a big Civil War enthusiast, and had noticed that there was a monument in a Nashville cemetery to the Sultana disaster. The survivors formed reunion groups, and one was based in the North, which would have been the Indiana, Ohio and Michigan survivors, and they met around Toledo, but the Southern guys from Kentucky and Tennessee mostly met in Knoxville. The last survivor died in 1931 and the actual survivor reunions ended.

Norman Shaw wondered how many descendants might still be interested in perpetuating the memory of the Sultana. He put a little blurb in a national newspaper: “I’m going to have a meeting, and anybody interested meet at this national cemetery monument.” He was flabbergasted that between 40 and 50 people showed up. He didn’t know what was gonna happen — he might have had one person or no people. Then he decided to do a formal sort of reunion in 1988. He put some ads out in Civil War magazines and more newspapers, and that’s where I saw it. I saw that they were having this reunion in 1988 through a Civil War magazine, and I called Norman and said, “Do you have to be a descendant? Or can anybody show up?” and Norman said, “Well, I’m not a descendant. I just have a love of history and a love of the Civil War, and now a love of the Sultana.”

I had been working on a database of who was on board the Sultana, and I went to the reunion and met another fellow Jerry Potter, from Memphis, who had discovered the wreck of the Sultana. The Sultana is actually underneath an Arkansas soybean field because it had sunk in the river and been covered over the years with silt and then the Mississippi changed course, so the Sultana is really about two miles inland from the Mississippi River itself. But that was how it started. Norman Shaw, just by accident, said, “Gee, I wonder if anybody’s interested in the Sultana,” and sure enough, over the years, we’ve grown to have descendants and enthusiasts from all over the United States.

What is the significance of this year’s reunion being in St. Louis?

This is the first time that we’re coming here. The Sultana had been built in February 1863 in Cincinnati, but eventually came down the Ohio River to Mississippi, and its home port became St. Louis. It was considered a cotton steamboat, and it would travel from St. Louis down to New Orleans on a regular schedule picking up passengers and cotton and whatever stuff that they could find and bring back and forth. The Sultana, her captain James Cass Mason and the chief clerk were from St. Louis. A lot of the crew men were from St. Louis. Some of them are even buried there. They would leave St. Louis and go down to Cairo — that’s where they heard about Lincoln’s assassination, then traveled all the way down to New Orleans. On their way back, they stopped at Vicksburg, where they overcrowded with almost 2,000 paroled union prisoners to take back north.

Unfortunately, on the trip down river, when the Sultana stopped at Vicksburg to report Lincoln’s assassination, an unscrupulous Illinois Captain Reuben Benton Hatch, a scoundrel, went on board and knew that Captain Mason was financially hurting, and he himself was financially hurting, and he knew that the government would be paying the steamboat captains to take a load up north so they could go home. These had been released prisoners of war from the horrors of Andersonville prison. They had suffered and they were pretty weak. So, Reuben Hatch meets with Mason and says, “The government will pay you to take 1,000 men up river. I know you’re going all the way down to New Orleans and then back up. If I can somehow save 1,000 men for you, could you give me a kickback?” There was a bribery offered, and Mason readily accepted.

Unfortunately, word of a bribe leaked out to some of the other officers, but they did not know it was the Sultana or Hatch. When the Sultana comes back up river, these officers say, “We’re going to try to head off this bribe and we’re going to put every last soldier on the Sultana,” which was exactly what Mason and Captain Hatch wanted. The more men, the more money they would make. Unfortunately, it ends up exploding.

The other one of the other reasons that we’re meeting in St. Louis is because St. Louis was the home of Julia Dent Grant, General Grant’s wife. General Grant was involved a little bit with the Sultana — he had at one point arrested Hatch. Captain Hatch was a quartermaster, a guy that would buy tents and horses and rent steamboats and get ice for the soldiers. He was buying stuff at one price but charging the government another price and pocketing the difference. Grant found out about this as his superior officer when they were at Cairo in 1861, and he had Hatch arrested. However, Hatch was a good friend of Abraham Lincoln, and Lincoln got Hatch released from arrest. So we know that if Grant’s arrest would have worked, Hatch would not have been in place, and perhaps the Sultana may not have gone down like that.

There’s only two known pictures of the Sultana, and one of them is the Sultana at the St. Louis waterfront. It’s not too far from where the Arch is, so we’re going to try to get our group to stand there and take a picture in the approximate location of the Sultana docked when that picture was taken in about 1864.

How many association members can trace their heritage back to the Sultana?

I would probably say 85 percent are descendants of Sultana people. On Saturday, at the very end, we have a candlelight memorial where we have one person from each family with a candle. I believe last time we had like 35 different families represented. We light their candle, and then they tell us as we light it who their ancestor was. Then we say, “If your ancestor perished please blow out your candle,” and all these candles go out so the only ones still lit are survivors. And then we say, “Now, since all the survivors are gone, please blow out your candles,” and they all do and it’s a very moving ceremony. You really see, at that point, how many people are represented.

In fact, this year we actually have a couple of people that are descendants of civilian passengers that were onboard the Sultana, not just the soldiers. The Sultana was also carrying paying passengers as well as crew members. We have about 65 people signed up, which is good.

Do you think sites like Ancestry.com are a factor in how many people are showing up?

Yes, I do. In fact, when we hear from people, they will say that, you know, I found out through Ancestry or I found out through Genealogy.com or even just on Facebook. “I noticed on Facebook, and I was wondering gee, I remember hearing the story from my great-great- grandmother of something about Sultana, but I didn’t know what it was,” so they started asking questions in their family. And then even websites like yours, that all helps to spread the word, and then somebody reaches out and says, “I remember hearing something about the Sultana years ago, let me track that down.” And next thing you know, they’re contacting us.

Is there any part of this history that I wouldn’t be able to find by looking at the Wikipedia page or maybe reading a book you’d recommend?

I maintain the Wikipedia page, so I know it’s accurate. Every now and then somebody will get in there and edit and put something in there. And I’m like, “Now, let’s take that out.” So I try to keep it as accurate as possible.

I think I would be careful in some of the some of the books that are out there, as well as some of the websites that are out there. It’s interesting. My first book came out in 1996. Even in that one, I thought there was about 1,700 people that were killed on board the Sultana, but over the years, I would see people would say 1,700 died. 1,800 died. 2,000 people died. And, “We think it was sabotaged: a boat was exploded by a Confederate saboteur.” And I said, “Wait a minute, first off, I know that it wasn’t sabotage. But how many people really did die?”

I began heavy research to try to come up with the most accurate list of who was on board and who survived and who perished. I started finding people that were supposedly dead, but they were getting a pension in 1880 and 1890, and their headstone says they died in 1915. Then they didn’t die on the Sultana. I was able to determine that 1,167 people died. So I would be cautious of looking at websites and books and magazine articles that still claim 1,700, 1,800, or 2,000 people died. … There was only one Union officer court martial for overcrowding the Sultana, and he was court martialed for the death of 1,100 people. So even back then they knew that it was only around 1,100 people.

Subscribe to Riverfront Times newsletters.Follow us: Apple News | Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter | Or sign up for our RSS Feed

[ad_2]

Source link

Entertainment

Five Fun Facts About Busch Stadium You Didn’t Know

[ad_1]

When baseball fans roll into St. Louis, Busch Stadium often tops their must-see list. But this iconic ballpark has more hidden gems beyond baseball — and even beyond its souvenir shops and good hotdogs. Here’s a lineup of interesting facts that’ll make you the MVP in Busch Stadium trivia.

From Ballpark to Brewing Brand Deal

A 1900 postcard showing the Oyster House of Tony Faust, founder of the brewing firm | Courtesy Anheuser-Busch.

Busch Stadium has a past that’s more refreshing than a cold beer. Before becoming the shrine of Cardinals baseball, it was a multipurpose park called Sportsman”s Park in 1953. Anheuser-Busch, the brewing giant that owned the Cardinals for a time, purchased the stadium and called it Busch Stadium.

Talk about brewing a partnership with a home run!

Museum for Baseball Maniacs

One can explore unique stadium models, step into the broadcast booth to relive Cardinals’ historic moments and hold authentic bats from team legends in this Museum | Courtesy Cardinals Nation

The St. Louis Cardinals Hall of Fame and Museum is an 8,000-square-foot tribute to baseball’s rich history. Opening on the Cardinals’ 2014 Opening Day, this shrine charts the team’s stories from its 1882 beginnings when it was still called the American Association Browns. Here, you can revel in the team’s 11 World Series Championships and 19 pennants. And if you’re feeling adventurous, watch the game from the museum’s roof—the Hoffmann Brothers Rooftop—complete with a full-service bar and an all-you-can-eat menu. It’s like VIP seating, but with more hot dogs.

Even the Fans Break World Records

Busch Stadium is more than a ballpark; it’s a record-breaking arena.

In one memorable event, Nathan’s Famous set a Guinness World Record for the most selfies taken simultaneously—4,296, to be exact. Just imagine trying to squeeze all those selfies into a single frame!

Not to be outdone, Edward Jones and the Alzheimer’s Association formed the largest human image of a brain on the field in 2018. With 1,202 people, the image was like a giant, multi-colored brain freeze.

1,202 people gathered in centerfield at Busch Stadium to form a multi-coloured brain image | Screenshot from Guinness World Records.

The MLB Park in Your Backyard

Are you an avid Cardinals fan, thinking about living near the stadium? The cost of living in the area might be in your favor.

A 2017 study by Estately.com shows that media prices for homes around Busch Stadium is the fourth least expensive among around 26 major MLB stadiums. When San Francisco Giants fans have to pay up $1,197,000 that year for the same convenience of catching a game at a walking distance, Cardinal fans can snag real estate at only $184,900. If that’s not a walk-off win of a deal, we’re not sure what is.

Big Cleats to Fill as Busch Stadium Eyes Expansion

Those wanting to invest in property near Busch Stadium better get it while it’s still affordable. Rumor has it Busch Stadium could soon expand. That rumor has been going around for three decades since talks to raise public money allegedly started. We’ll believe it when we see it.

According to Cardinals owner Bill DeWitt III, plans are likely to mirror recent projects for the Milwaukee Brewers and Baltimore Orioles, with price tags hovering around $500 to $600 million. But the real investment is still up for debates pending a concrete cost-benefit analysis on the stadium’s surrounding area.

So the next time you kick back with a cold beer and catch a game at Busch Stadium, be in awe of the fact there’s more to the place than what meets the batter’s eye. Pitch these interesting facts at trivia night or to your Hinge date who’s new in town. Who knows – you might just win a home run beer.

[ad_2]

Source link

Entertainment

Nashville Police Officer Arrested for Appearing in Adult Video

[ad_1]

A Nashville police officer, Sean Herman, 33, has been arrested and charged with two counts of felony official misconduct after allegedly appearing in an adult video on OnlyFans while on duty. Herman was fired one day after detectives became aware of the video last month.

The video, titled “Can’t believe he didn’t arrest me,” shows Herman, participating in a mock traffic stop while in uniform, groping a woman’s breasts, and grabbing his genitals through his pants. The officer’s face is not visible, but his cruiser, patrol car, and Metro Nashville Police Department patch on his shoulder are clearly visible.

The Metro Nashville Police Department launched an investigation immediately upon discovering the video. The internal investigation determined Herman to be the officer appearing in the video. He was fired on May 9 and arrested on June 14, with a bond set at $3,000.

Subscribe to Riverfront Times newsletters.Follow us: Apple News | Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter | Or sign up for our RSS Feed

[ad_2]

Source link

Entertainment

Jane Smiley’s New Novel, Lucky, Draws on Her Charmed St. Louis Childhood

[ad_1]

Like any good St. Louisan, Jane Smiley has an opinion on the high school question.

“If you ask somebody in St. Louis, ‘Where did you go to high school’ — because each school is so unique, you do get a sense of what their life was like and where they live,” says the John Burroughs graduate. “Where are you from? What do you like? And, you know, the answer is always interesting.”

That’s pretty much what Jodie Rattler, the main character of Smiley’s latest novel, Lucky, thinks.

“School, in St. Louis, is a big question, especially high school,” Rattler muses toward the start of the story. “… My theory about this is not that the person who asks wants to judge you for your socioeconomic position, rather that he or she wants to imagine your neighborhood, since there are so many, and they are all different.”

This parallel thought pattern is even less of a coincidence than the author/subject relationship implies. Lucky, which Alfred A. Knopf published last month, is nominally the story of Jodie, a folk musician gone fairly big who hails from our fair town. But the book is more than just its plot: It’s an ode to St. Louis and an exploration of the life Jane Smiley might have lived — if only a few things were different.

The trail to Lucky started in 2019, when Smiley returned here for her 50th high school reunion and agreed to a local interview. The radio host asked why she’d never set a novel in St. Louis.

“I thought, ‘Boy, why haven’t I done that?'” Smiley remembers. “And so then I thought, ‘Well, maybe I should think about it.’ And I decided since I love music, and St. Louis is a great music town, that I would maybe do an alternative biography of myself if I had been a musician, and of course I would say where she went to [high] school. So that’s what got me started. And the more I got into it, the more I enjoyed it.” click to enlarge DEREK SHAPTON Jane Smiley rocketed to literary stardom after winning the Pulitzer Prize for fiction for A Thousand Acres. She now has more than 25 books to her name.

The Life Jane Smiley Didn’t Live

Jane Smiley has always felt really lucky.

First, there was her background: She grew up with a “very easygoing and fun family.” Growing up in Webster Groves, she enjoyed wandering through the adjacent neighborhoods and exploring how spaces that were so close together could have such different vibes.

Then there was her career, which kicked into gear when she was 42 with the publication of A Thousand Acres, a retelling of King Lear set on a farm in Iowa. It won the National Book Critics Circle Award for fiction in 1991 and the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1992. It became a movie and, two years ago, an opera. Since then, she’s been steadily publishing and now has more than 25 books to her name.

“I was lucky in the way that my career got started,” Smiley says. “It was lucky in a way that it continued. I was lucky to win the Pulitzer. And I really enjoyed that. I said, ‘OK, I want to write about someone who’s lucky, but I don’t want it to be me. Because I want to contemplate the idea of luck, and see how maybe it works for somebody else.'”

click to enlarge

Both the book, and Jodie’s good luck, start at Cahokia Downs in 1955. Jodie’s Uncle Drew, a father stand-in, takes her to the racetrack and has her select the numbers on a bet that turns his last $6 into $5,986. She gets $86 of the winnings in a roll of $2 bills.

Smiley, a horse lover throughout her life, used to love looking at the horses at the racetrack before she understood how “corrupt it is at work.” (She also reminisces about pony rides at the corner of Brentwood and Manchester across from St. Mary Magdalen Church and riding her horse at Otis Brown Stables.)

Unlike Smiley, Jodie is not a horse person. And at first, Jodie feels somewhat disconnected from her luck — it’s something other people tell her that she possesses. She’s lucky to live where she does. She’s lucky that her mom doesn’t make her clear her plate, that her uncle has a big house, that she gets into John Burroughs. Later, she begins to carry those bills around as a talisman.

“[I] made a vow never to spend that roll of two-dollar bills — that was where the luck lived,” Jodie thinks after a narrow miss with a tornado.

It’s John Burroughs that changes Jodie’s life, just as it did Smiley’s. But instead of falling in love with books in high school and becoming a writer, Jodie falls into music. She eventually gets into songwriting, penning tunes as a sophomore at Penn State that launch her career.

One of Jodie’s songs should instantly resonate for St. Louis readers.

“The third one was about an accident I heard had happened in St. Louis,” Jodie recalls in the book, “a car going off the bridge over the River des Peres, which may have once been a river but was now a sewer. My challenge was to make sense of the story while sticking in a bunch of odd St. Louis street names — Skinker, of course, DeBaliviere, Bompart, Chouteau, Vandeventer. The chorus was about Big Bend. The song made me cry, but I never sang it to anyone but myself.”

Throughout the book are Jodie’s lyrics, alongside the events that inspire them. Writing them was a new experience for Smiley, who found herself picking up a banjo gifted by an ex and strumming the few songs she’d managed to learn, as well as revisiting the popular music of the novel’s time — the Beatles (George is Smiley’s favorite), Janis Joplin and the Traveling Wilburys, along with Judy Collins, Joan Baez, Joni Mitchell, and Peter, Paul and Mary — basically “all the folk singers.”

“I really love music, and I do wish I’d managed to practice, which I was always a failure at,” Smiley says. “… I liked that they made up their own lyrics, and they made their own music, and I was impressed by that.”

Both Smiley and Jodie grew up in households replete with record players and music. It’s one of their great commonalities.

A great difference between the two? That would be sex. At one point, Jodie compares her body count, which she calls the “Jodie Club,” with a lover — 25 (rounded up, Jodie notes) to his 150.

“That was a lot of fun,” says Smiley. “She learns a lot from having those affairs, and she enjoys it. She’s careful. And I like the fact that she never gets married, and she doesn’t really have any regrets about that.” (Smiley has been married four times.) “In some sense, her musical career has made her want to explore those kinds of issues of love and connection and sex and the way guys are.”

You can tell Smiley had a good time writing this. After Jodie loses her virginity, she thinks, “The erection had turned into a rather cute thing that flopped to one side.”

“Oh, it was fun,” Smiley confirms. “Sometimes I would say, ‘OK, what can I have Jodie do next? What’s something completely different than what I did when I was her age?’ And then I’d have to think about that and try and come up with something that was actually interesting. I knew that she couldn’t do all the things that I had done, and she had to be kind of a different person than I was. And so I made her a little more independent, and a little more determined.”

click to enlarge VIA THE SCHOOL YEARBOOK Jane Smiley’s high school yearbook photo. In Lucky, Jodie recalls of a classmate, “The gawky girl had stuck her head into a basketball basket, taken hold of the rim, and her caption was, ‘They always have the tall girls guard the basket.'”

Lucky follows Jodie from childhood to into her late 60s. At several points in the novel, she crosses paths with a Burroughs classmate, identified only as the “gawky girl.” Jodie takes note of her former classmate, but she’s not recognized.

Toward the end, Jodie walks into Left Bank Books and sees the gawky girl’s name on the cover of a novel.

“Out of curiosity, I read a few things about the gawky girl. Apparently she really had been to Greenland, and the Pulitzer novel was based on King Lear, which I thought was weird, but I did remember that when we read King Lear in senior English, I hadn’t liked it,” Jodie thinks. “… I remembered walking past her in the front hall of the school, maybe a ways down from the front door. She was standing there smiling, her glasses sliding down her nose, and one of the guys in our class, one of the outgoing ones, not one of the math nerds that abounded, stopped and looked at her, and said, ‘You know, I would date you if you weren’t so tall.'”

Sound familiar? Does it help to know Smiley is 6’2″?

The doppelgangers meet face to face after their 50th Burroughs’ reunion at the Fox and Hounds bar at the Cheshire. To go into what happens next — it’s too much of a spoiler.

“In every book, there’s always a surprise,” Smiley says. click to enlarge ZACHARY LINHARES Smiley enjoys St. Louis place names, and DeBaliviere is one of many in the novel.

Jodie Rattler’s St. Louis

Lucky is a smorgasbord of familiar names and places for St. Louis readers, and picking them out will be a big part of the joy of the book for locals.

“I love many things about St. Louis — not exactly the humidity, but lots of other things,” Smiley says. “One of the things I love is how weird the street names are. So I had to put her in that house on Skinker, and I had to refer to a few other places that are kind of weird. I couldn’t fit them all in.

“But I love the way that those street names and St. Louis are a real mix, and some of them are true French street names. Some of them are true English street names. Like Grav-wah or Grav-whoy” — here she deploys first the French and then the St. Louis version of “Gravois” — “whatever you want to call it, and Clark. It’s just really interesting to look around there and sense all of the different cultures that lived there and went through there.”

Jodie grows up in a house on Skinker near Big Bend. It’s “a pale golden color, with the tile roof and the little balcony,” Smiley writes. Jodie walks through Forest Park and eats at Schneithorst’s. Her mother works at the Muny; she shops at Famous Barr. Her grandfather prefers the “golf course near our house on Skinker,” which must be the Forest Park course. Jodie goes to Cardinals games, the Saint Louis Zoo and Grant’s Farm. She visits and thinks about St. Louis’ parks such as Tilles and Babler. Even the county jail in Clayton gets a mention.

Of course, Chuck Berry shows up several times, first mentioned for getting “in trouble for doing something that I wouldn’t understand.” Later, as Jodie drives by his home, she drops some shade on the county along the way: “Aunt Louise knew where Phyllis Schlafly’s house was, so I drove past there — another reason not to choose Ladue,” she writes.

Jodie and the man who invented rock & roll later meet face-to-face briefly at a festival near San Jose, California. “My favorite parts were getting to walk up to Chuck Berry and say, ‘I’m from St. Louis, too. Skinker!’ and having him reply, ‘Cards, baby!’ and know that no one nearby knew what in the world we were talking about,” Jodie recalls.

Lucky feels like a bit of a members-only club, and here the club is St. Louis. There is barely a page that is without some kind of reference — to the point where one might wonder if non-locals can even keep up. (Though they should rest assured: It’s a good read.)

“I write more or less to do what I want to do, and so I wrote about the things that interested me,” Smiley says. And more than 50 years after she graduated high school and left Webster Groves for Iowa and (briefly) Iceland and California, where she lives today, St. Louis, clearly, qualifies.

Subscribe to Riverfront Times newsletters.Follow us: Apple News | Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter | Or sign up for our RSS Feed

[ad_2]

Source link

-

Politics2 years ago

Politics2 years agoPrenzler ‘reconsidered’ campaign donors, accepts vendor funds

-

Board Bills1 year ago

2024-2025 Board Bill 80 — Prohibiting Street Takeovers

-

Board Bills3 years ago

Board Bills3 years ago2022-2023 Board Bill 168 — City’s Capital Fund

-

Business3 years ago

Business3 years agoFields Foods to open new grocery in Pagedale in March

-

Business3 years ago

Business3 years agoWe Live Here Auténtico! | The Hispanic Chamber | Community and Connection Central

-

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment2 years agoOK, That New Cardinals/Nelly City Connect Collab Is Kind of Great

-

Entertainment3 years ago

Entertainment3 years agoSt.Louis Man Sounds Just Like Whitley Hewsten, Plans on Performing At The Shayfitz Arena.

-

Local News2 years ago

Local News2 years agoFox 2 Reporter Tim Ezell Reveals He Has Parkinson’s Disease | St. Louis Metro News | St. Louis