Politics

Missouri ditched an election partnership, creating voter limbo

[ad_1]

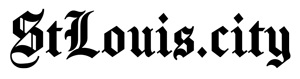

This article was originally published by the The Center for Public Integrity, a nonprofit investigative news organization based in Washington, D.C.” The link for “Center for Public Integrity” must link to our homepage.ST. LOUIS — Eric Fey is bracing for Election Day snarls because of a decision his state made last year.Missouri pulled out of a collaboration known as the Electronic Registration Information Center, or ERIC, which helps states keep voter rolls accurate — such as flagging when people move. Fey, the Democratic director of elections in St. Louis County, expects delays when people discover at the polls that the address on their voter registration record is incorrect.“More people will be doing change-of-address forms at polling places and at the election office on Election Day,” said Fey, who is also president of a statewide local election authorities group. “At least for those voters, it takes longer, and there is a longer line.”Missouri and eight other states — Alabama, Florida, Iowa, Louisiana, Ohio, Texas, Virginia and West Virginia — left ERIC in the last two years.The move, driven by Republican leaders, followed on the heels of a baseless article published by a St. Louis conservative website that alleged ERIC is a left-wing plot funded by billionaire George Soros, who is often the target of antisemitic conspiracies.In fact, ERIC is funded by its member states — now 24 of them, plus Washington, D.C. — and helps them kick ineligible voters off the rolls as well as register new ones. It received startup funding years ago from The Pew Charitable Trusts, which has over its history partnered with Soros’ Open Society Foundations along with many other funders, including conservative ones.

Stephanie Lecci

/

St. Louis Public Radio Eric Fey, Democratic director of the St. Louis County Board of Elections, demonstrates how to select an audio ballot versus the large-print option on the iVotronic system.

In Missouri, local election officials who must deal with the consequences of losing access to ERIC’s tools weren’t consulted on the decision to leave the collaboration. That’s according to a highly critical January report from the state’s Republican auditor, who said there were no plans “to fully replace the benefits received from the membership.”Duplicating what ERIC does is difficult. Secretaries of states that left ERIC have tried to find or create another system that does the same data-matching and cleaning — and failed. When states leave ERIC without an effective replacement, it can make their voter databases less accurate. That in turn can feed bad-faith arguments about election fraud, experts worry, in an environment where such arguments have already been used to justify voting restrictions in multiple states.Another underappreciated consequence is the one worrying Fey: People in those states who haven’t updated their voter registration after moving will likely find it more challenging to cast a ballot.Census data shows the problem disproportionately affects people of color, low-income Americans and younger people because they move more frequently. Voters in those groups are more likely to register as Democrats and have long experienced a host of voter-suppression tactics.“Mobility is the biggest challenge election officials face in terms of keeping accurate voter lists. Routine, quality list maintenance is especially important with highly mobile populations,” said Shane Hamlin, executive director of ERIC, in an email to the Center for Public Integrity.It also means more challenges for local election offices. In St. Louis County, it’s up to Fey, his Republican counterpart Rick Stream and their staff to update the records, which eventually go into Missouri’s statewide voter registration database. The office used to have help with this massive task through ERIC. Now it doesn’t.“Many people in the 21st century feel like, ‘I updated my address with pick-your-other-government-agency, but it doesn’t get to the election office. I thought I did all this stuff. Why don’t you have my information updated?’” Fey noted.Stream also saw ERIC as a beneficial tool. He thinks it is unfortunate the state left the effort.“It gave us information that we couldn’t have received any other way,” Stream said. “ERIC was good in that it crossed state lines.”

Dominick Williams

/

Special to the St. Louis Public RadioMissouri Republican Secretary of State Jay Ashcroft speaks with potential voters on Feb. 17 at a Governor’s Forum in Kansas City.

Missouri Secretary of State Jay Ashcroft, who was in his first year in that office when the state joined ERIC, made the decision to pull out. He said in an interview that he doesn’t remember if he consulted with local election authorities about that decision.“It’s not something you would normally consult them on,” said Ashcroft, who said he instead talked to other secretaries of state and his office’s information technology staff. “It’s not their work. I am responsible for the statewide voter registration system.”But local election authorities are responsible for keeping voter rolls up to date in their jurisdictions. It’s that data that feeds into the statewide system.Ashcroft confirmed that local election authorities are the only ones who add or remove voters from the rolls in Missouri.“When there are well-defined, credible opportunities to promote voting, he is going in the opposite direction,” said Nimrod “Rod” Chapel, a lawyer and president of the Missouri State Conference of the NAACP, who is concerned about the departure from ERIC. “It’s going to hurt all Missourians, but without a doubt Black and brown Missourians who are moving at greater rates, whether to find jobs or communities that they can live in.”Here’s the problem states face: While the Help America Vote Act of 2002 requires states to implement electronic voter registration databases, it does not require them to format the data in a way that allows for comparisons. That complicates efforts to determine if a voter has left one state for another. The federal government also doesn’t provide all the information states need to keep their voter rolls up to date.“These are issues that have fallen under the radar,” said Michael Morse, a lawyer and political scientist who teaches election law at the University of Pennsylvania.ERIC was built to address these problems. Election-Day voter registration, which includes the last-minute address updates that Fey is worried about, dropped in Minnesota after the state joined ERIC in 2014. These same-day registrations accounted for more than 10% of total votes in the two elections before that year. They fell to less than 6% by 2022.When other states leave ERIC, it affects not only them but also the states that remain, said David Maeda, the Minnesota elections director and secretary of ERIC. For every state that leaves, that’s one less to check with for Minnesotans who moved.“It’s been a really difficult year for all of us in it,” Maeda said. “We’re getting less data — including the very large Florida and Texas.”

Mobile voters a challenge for election officialsVoters whose information is out-of-date in their state’s voter registration database may end up traveling to multiple locations on Election Day just to cast a ballot. They can’t request a mail-in ballot. They won’t receive election-related mail. Canvassing candidates or issue-focused petitioners will not be able to seek them out to talk about policy ahead of the election.“If we want these key voting blocs to turn out in November, we need to make sure they hear early and often from local organizers and trusted messengers in their own communities,” said Zo Tobi, director of donor organizing for the Movement Voter Project, which invests in voter groups focused on often-marginalized populations such as youth and communities of color.The impact for voters won’t be clear until they attempt to vote. There’s no way to know yet how much change-of-address work is backing up in local election offices that no longer have access to ERIC.David Becker, founder of the Center for Election Innovation and Research, helped launch ERIC while director of Pew’s elections program. He expects longer lines and more provisional ballots, offered to people when certain registration issues crop up. Such ballots take longer for voters to fill out and have a higher chance of not being counted.Keeping voter registration databases up-to-date is never-ending work. A Pew Charitable Trusts report from 2012, the year ERIC launched, estimated that one out of every eight voter registration records in the U.S. was inaccurate.That need to conduct regular “list maintenance” is regulated by the National Voter Registration Act of 1993, known as the motor voter law.

Brian Munoz

/

St. Louis Public RadioThe St. Louis Board of Election Commissioners Building on September 2021 in downtown St. Louis.

The law requires states to appoint a chief official to oversee elections. The official is also charged with making sure the state makes a “reasonable effort” to identify voters who have entered the prison system, moved, died or become otherwise unable to vote.One stark example that crossed the line: Leading up to the 2000 presidential election, officials in the city of St. Louis moved more than 30,000 voters to “inactive” lists, alarming Black leaders. On Election Day, hundreds of people couldn’t vote. Poll workers calling headquarters to verify eligibility couldn’t get through on jammed lines.Voters sent to the election board’s main office in downtown St. Louis to plead their case were still standing in line at 10 p.m. trying to vote.In the fraught aftermath, a federal consent decree required St. Louis Board of Election commissioners to change their policies for maintaining accurate registration records and properly notify voters of their registration status.In the book “Keeping Down the Black Vote,” authors Frances Fox Piven, Lorraine C. Minnite and Margaret Groarke argue that election officials are far quicker to purge than to make sure everyone gets the opportunity to register.Federal law contributes to disparities in registration rates.For instance, the motor voter law requires states to offer voter registration at driver’s license facilities in a way that integrates it with those agencies’ own applications for a seamless experience. For public assistance offices and disability agencies, the law requires only that they offer separate voter registration forms. And those are places more likely to reach lower-income people.A requirement for registration options at unemployment offices was pulled from the bill by Senate Republicans before it passed, according to “Keeping Down the Black Vote.”“California Republican Bill Thomas [of the House of Representatives] said, ‘All of us are interested in extending the right to vote to all. But at unemployment and welfare offices only? … If you want to pick a party affiliation of these people, take a guess. You won’t pick ours,’” the book’s authors noted, citing news coverage at the time.

Danny Wicentowski

/

St. Louis Public RadioGateway Pundit owner Jim Hoft speaks at a political rally in support of Donald Trump in 2016.

‘Horrible and misleading’ informationThe St. Louis-based site that published the series about ERIC, the Gateway Pundit, grew in popularity after promoting lies about the 2020 election. In 2021, a Reuters investigation found the Gateway Pundit cited in more than 100 threatening and hostile communications toward local election workers since that election. The website is now the subject of two defamation lawsuits.Its ERIC pieces began publishing on Jan. 20, 2022, and within a week Louisiana Secretary of State Kyle Ardoin ended the state’s membership. Ardoin’s spokesman told Votebeat the decision had nothing to do with the Gateway Pundit. Alabama followed nearly a year later.In March 2023, Trump used his Truth Social platform to encourage states to end their membership, saying without evidence that it “‘pumps the rolls’ for Democrats and does nothing to clean them up.”The same day, Florida, Missouri and West Virginia officials all released statements that they were leaving ERIC — Missouri’s secretary of state said he was leading them in doing so. Iowa, Ohio, Virginia and Texas withdrew over the next several months.The watchdog group American Oversight obtained emails from Ashcroft’s office that show one of his top lieutenants expressing concern before the state pulled out from ERIC about the “horrible and misleading” information circulating about the organization.“ERIC is never connected to any state’s voter registration system,” Hamlin, ERIC’s executive director, wrote in an open letter on the organization’s website as misinformation mounted. “Members retain complete control over their voter rolls and they use the reports we provide in ways that comply with federal and state laws.”

Brian Munoz

/

St. Louis Public RadioVoting machines in September 2022 at the St. Louis Public Library in the city’s Carondelet neighborhood.

For states that left ERIC, trying to recreate in short order what officials there spent years and millions of dollars developing has not gone well.“Virginia paid $29,000 in September to regain access to just a sliver of the data they used to obtain via the Electronic Registration Information Center, or ERIC,” Votebeat reported in December. “Alabama and Missouri officials took months to come up with new plans for cleaning voter rolls, landing on plans that are less rigorous than ERIC.”Public Integrity requested any documents from the Missouri Secretary of State’s office detailing current voter list maintenance efforts. The agency said some information could not be released publicly but provided a memo sent to local election officials. That memo, said St. Louis County’s Fey, had no additional guidance or assistance beyond what the state offered while an ERIC member — but without the tools ERIC provided.Ashcroft, the Missouri secretary of state, said he is “looking at other ways to get and massage the data.” But he said the local offices still receive change-of-address and death reports as they did both before and during the state’s ERIC membership. He said he thought the reports are “indistinguishable” from ERIC’s.“I don’t think there is a vacuum left by ERIC,” he said.Brianna Lennon, the county clerk in Boone County, Missouri, disagrees that the information local officials receive now is equally good.“The reports look the same, but the background data is not the same because there’s no information to show where people died out of state,” said Lennon, previously the state’s deputy director of elections.Boone County, home to the University of Missouri-Columbia, benefited from ERIC in a number of ways, she said.“Because we are a college town, people do change addresses quite a bit,” Lennon said.

Brian Munoz

/

St. Louis Public RadioDavid Torres, 29, a doctoral candidate in civil engineering from Mexico City, Mexico, walks past the University of Missouri’s columns in December 2021 at the campus in Columbia, Mo.

One tool pitched to election officials as an ERIC alternative is EagleAI. It’s supported by Cleta Mitchell, who aided former President Donald Trump’s efforts to overturn the 2020 election results and, Rolling Stone magazine reported, pressed state officials to leave ERIC. States that did so “no longer have the burden” of offering voter registration to the lion’s share of citizens who are eligible but haven’t registered, Mitchell said in an emailed response to Public Integrity. She also claimed that those states are doing as well as or better with list maintenance as before.EagleAI performs matches with public data such as property records. That type of matching, election experts warn, produces too many false positives to be used as a reliable method for cleaning voter registration databases.Anyone familiar with the history of list maintenance knows how easily it can go off the rails.Shortly after the Help America Vote Act passed in 2002, Kansas officials signed agreements with Iowa, Nebraska and Missouri and began sharing data for such work through a program known as Interstate CrossCheck.In 2019, it was shut down. A federal audit found security vulnerabilities, and voters sued after portions of their Social Security numbers were exposed.Now, some former ERIC states — such as Ohio, West Virginia, Virginia and Florida — are creating data-sharing agreements that strike David Kimball, a political science professor at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, as a worrisome echo of that history.“States doing these new agreements are basically doing the same thing as what Kansas CrossCheck was, and we already know it was no good,” Kimball said. “I don’t know what they expect, other than to sow distrust in voting systems.”

Brian Munoz

/

St. Louis Public RadioNatalie Noblett, 61, of the St. Louis’ Carondelet neighborhood, places an American flag on a “vote here” sign in September 202 at the St. Louis Public Library in south St. Louis.

Ashcroft, the Missouri secretary of state, didn’t like a commitment members have to make when they join ERIC: attempt to reach out to 95% of eligible but unregistered voters in the state to provide them information about how to register.In his 2023 letter about ending the state’s membership, he said ERIC “focuses” on adding names to voter rolls by requiring states to contact individuals who “already had an opportunity to register to vote and made the conscious decision to not be registered.”In fact, the ERIC bylaws attempt to make sure its members aren’t bothering people.“Members shall not be required to initiate contact with eligible or possibly eligible voters more than once at the same address,” the bylaws note, “nor shall members be required to contact any individual who has affirmatively confirmed their desire not to be contacted for purposes of voter registration.”Asked why he doesn’t want to do that outreach, Ashcroft said Missourians don’t need it.“Everybody has a chance to [register to] vote all the time,” Ashcroft said. “They can do it on their cell phones or smartphones, they can do it on their computer. That’s a disingenuous question.”The Center for Public Integrity is a nonprofit investigative news organization that receives support from readers and foundations. It has in the past received grants from the Open Society Foundations, most recently in 2015, and Pew Charitable Trusts, most recently in 2010, both mentioned in this story. Donors do not dictate coverage.

[ad_2]

Source link

Politics

Poll: Support for Missouri abortion rights amendment growing

[ad_1]

A proposed constitutional amendment legalizing abortion in Missouri received support from more than half of respondents in a new poll from St. Louis University and YouGov.That’s a boost from a poll earlier this year, which could mean what’s known as Amendment 3 is in a solid position to pass in November.SLU/YouGov’s poll of 900 likely Missouri voters from Aug. 8-16 found that 52% of respondents would vote for Amendment 3, which would place constitutional protections for abortion up to fetal viability. Thirty-four percent would vote against the measure, while 14% aren’t sure.By comparison, the SLU/YouGov poll from February found that 44% of voters would back the abortion legalization amendment.St. Louis University political science professor Steven Rogers said 32% of Republicans and 53% of independents would vote for the amendment. That’s in addition to nearly 80% of Democratic respondents who would approve the measure. In the previous poll, 24% of Republicans supported the amendment.Rogers noted that neither Amendment 3 nor a separate ballot item raising the state’s minimum wage is helping Democratic candidates. GOP contenders for U.S. Senate, governor, lieutenant governor, treasurer and secretary of state all hold comfortable leads.“We are seeing this kind of crossover voting, a little bit, where there are voters who are basically saying, ‘I am going to the polls and I’m going to support a Republican candidate, but I’m also going to go to the polls and then I’m also going to try to expand abortion access and then raise the minimum wage,’” Rogers said.Republican gubernatorial nominee Mike Kehoe has a 51%-41% lead over Democrat Crystal Quade. And U.S. Sen. Josh Hawley is leading Democrat Lucas Kunce by 53% to 42%. Some GOP candidates for attorney general, secretary of state and treasurer have even larger leads over their Democratic rivals.

Brian Munoz

/

St. Louis Public RadioHundreds of demonstrators pack into a parking lot at Planned Parenthood of St. Louis and Southwest Missouri on June 24, 2022, during a demonstration following the Supreme Court’s reversal of a case that guaranteed the constitutional right to an abortion.

One of the biggest challenges for foes of Amendment 3 could be financial.Typically, Missouri ballot initiatives with well-funded and well-organized campaigns have a better chance of passing — especially if the opposition is underfunded and disorganized. Since the end of July, the campaign committee formed to pass Amendment 3 received more than $3 million in donations of $5,000 or more.That money could be used for television advertisements to improve the proposal’s standing further, Rogers said, as well as point out that Missouri’s current abortion ban doesn’t allow the procedure in the case of rape or incest.“Meanwhile, the anti side won’t have those resources to kind of try to make that counter argument as strongly, and they don’t have public opinion as strongly on their side,” Rogers said.There is precedent of a well-funded initiative almost failing due to opposition from socially conservative voters.In 2006, a measure providing constitutional protections for embryonic stem cell research nearly failed — even though a campaign committee aimed at passing it had a commanding financial advantage.Former state Sen. Bob Onder was part of the opposition campaign to that measure. He said earlier this month it is possible to create a similar dynamic in 2024 against Amendment 3, if social conservatives who oppose abortion rights can band together.“This is not about reproductive rights or care for miscarriages or IVF or anything else,” said Onder, the GOP nominee for Missouri’s 3rd Congressional District seat. “Missourians will learn that out-of-state special interests and dark money from out of state is lying to them and they will reject this amendment.”Quade said earlier this month that Missourians of all political ideologies are ready to roll back the state’s abortion ban.“Regardless of political party, we hear from folks who are tired of politicians being in their doctor’s offices,” Quade said. “They want politicians to mind their own business. So this is going to excite folks all across the political spectrum.”

[ad_2]

Source link

Politics

Democrat Mark Osmack makes his case for Missouri treasurer

[ad_1]

Mark Osmack has been out of the electoral fray for awhile, but he never completely abandoned his passion for Missouri politics.Osmack, a Valley Park native and U.S. Army veteran, previously ran for Missouri’s 2nd Congressional District seat and for state Senate. Now he’s the Democratic nominee for state treasurer after receiving a phone call from Missouri Democratic Party Chairman Russ Carnahan asking him to run.“There’s a lot of decision making and processing and evaluation that goes into it, which is something I am very passionate and interested in,” Osmack said this week on an episode of Politically Speaking.Osmack is squaring off against state Treasurer Vivek Malek, who was able to easily win a crowded GOP primary against several veteran lawmakers including House Budget Chairman Cody Smith and state Sen. Andrew Koenig.While Malek was able to attract big donations to his political action committee and pour his own money into the campaign, Osmack isn’t worried that he won’t be able to compete in November. Since Malek was appointed to his post, Osmack contends he hasn’t proven that he’s a formidable opponent in a general election.“His actions and his decision making so far in his roughly two year tenure in that office have been questionable,” Osmack said.Among other things, Osmack was critical of Malek for placing unclaimed property notices on video gaming machines which are usually found in gas stations or convenience stores. The legality of the machines has been questioned for some time.As Malek explained on his own episode of Politically Speaking, he wanted to make sure the unclaimed property program was as widely advertised as possible. But he acknowledged it was a mistake to put the decals close to the machines and ultimately decided to remove them.Osmack said: “This doesn’t even pass the common sense sniff test of, ‘Hey, should I put state stickers claiming you might have a billion dollars on a gambling machine that is not registered with the state of Missouri?’ If we’re gonna give kudos for him acknowledging the wrong thing, it never should have been done in the first place.”Osmack’s platform includes supporting programs providing school meals using Missouri agriculture products and making child care more accessible for the working class.He said the fact that Missouri has such a large surplus shows that it’s possible to create programs to make child care within reach for parents.“It is quite audacious for [Republicans] to brag about $8 billion, with a B, dollars in state surplus, while we offer next to no social services to include pre-K, daycare, or child care,” Osmack said.Here’s are some other topics Osmack discussed on the show:How he would handle managing the state’s pension systems and approving low-income housing tax credits. The state treasurer’s office is on boards overseeing both of those programs.Malek’s decision to cut off investments from Chinese companies. Osmack said that Missouri needs to be cautious about abandoning China as a business partner, especially since they’re a major consumer of the state’s agriculture products. “There’s a way to make this work where we are not supporting communist nations to the detriment of the United States or our allies, while also maintaining strong economic ties that benefit Missouri farmers,” he said.What it was like to witness the skirmish at the Missouri State Fair between U.S. Sen. Josh Hawley and Democratic challenger Lucas Kunce.Whether Kunce can get the support of influential groups like the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee, which often channels money and staff to states with competitive Senate elections.

[ad_2]

Source link

Politics

As Illinois receives praise for its cannabis equity efforts, stakeholders work on system’s flaws

[ad_1]

Medical marijuana patients can now purchase cannabis grown by small businesses as part of their allotment, Illinois’ top cannabis regulator said, but smaller, newly licensed cannabis growers are still seeking greater access to the state’s medical marijuana customers.Illinois legalized medicinal marijuana beginning in 2014, then legalized it for recreational use in 2020. While the 2020 law legalized cannabis use for any adult age 21 or older, it did not expand licensing for medical dispensaries.Patients can purchase marijuana as part of the medical cannabis program at dual-purpose dispensaries, which are licensed to serve both medical and recreational customers. But dual-purpose dispensaries are greatly outnumbered by dispensaries only licensed to sell recreationally, and there are no medical-only dispensaries in the state.As another part of the adult-use legalization law, lawmakers created a “craft grow” license category that was designed to give more opportunities to Illinoisans hoping to legally grow and sell marijuana. The smaller-scale grow operations were part of the 2020 law’s efforts to diversify the cannabis industry in Illinois.Prior to that, all cultivation centers in Illinois were large-scale operations dominated by large multi-state operators. The existing cultivators, mostly in operation since 2014, were allowed to grow recreational cannabis beginning in 2019.Until recently, dual-purpose dispensaries have been unsure as to whether craft-grown products, made by social equity licensees — those who have lived in a disproportionately impacted area or have been historically impacted by the war on drugs — can be sold medicinally as part of a patient’s medical allotment.Erin Johnson, the state’s cannabis regulation oversight officer, told Capitol News Illinois last month that her office has “been telling dispensaries, as they have been asking us” they can now sell craft-grown products to medical patients.“There was just a track and trace issue on our end, but never anything statutorily,” she said.

Dilpreet Raju

/

Capitol News IllinoisThe graphic shows how cannabis grown in Illinois gets from cultivation centers to customers.

No notice has been posted, but Johnson’s verbal guidance comes almost two years after the first craft grow business went online in Illinois.It allows roughly 150,000 medical patients, who dispensary owners say are the most consistent purchasers of marijuana, to buy products made by social equity businesses without paying recreational taxes. However — even as more dispensaries open — the number available to medical patients has not increased since 2018, something the Cannabis Regulation Oversight Office “desperately” wants to see changed. Johnson said Illinois is a limited license state, meaning “there are caps on everything” to help control the relatively new market.Berwyn Thompkins, who operates two cannabis businesses, said the rules limited options for patients and small businesses.“It’s about access,” Thompkins said. “Why wouldn’t we want all the patients — which the (adult-use) program was initially built around — why wouldn’t we want them to have access? They should have access to any dispensary.”Customers with a medical marijuana card pay a 1% tax on all marijuana products, whereas recreational customers pay retail taxes between roughly 20 and 40% on a given cannabis product, when accounting for local taxes.While Illinois has received praise for its equity-focused cannabis law, including through an independent study that showed more people of color own cannabis licenses than in any other state, some industry operators say they’ve experienced many unnecessary hurdles getting their businesses up and running.The state, in fact, announced last month that it had opened its 100th social equity dispensary.But Steve Olson, purchasing manager at a pair of dispensaries (including one dual-purpose dispensary) near Rockford, said small specialty license holders have been left in the lurch since the first craft grower opened in October 2022.“You would think that this would be something they’re (the government) trying to help out these social equity companies with, but they’re putting handcuffs on them in so many different spots,” he said. “One of them being this medical thing.”Olson said he contacted state agencies, including the Department of Financial and Professional Regulation, months ago about whether craft products can be sold to medical patients at their retail tax rate, but only heard one response: “They all say it was an oversight.”This potentially hurt social equity companies because they sell wholesale to dispensaries and may have been missing out on a consistent customer base through those medical dispensaries.Olson said the state’s attempts to provide licensees with a path to a successful business over the years, such as with corrective lotteries that granted more social equity licenses, have come up short.“It’s like they almost set up the social equity thing to fail so the big guys could come in and swoop up all these licenses,” Olson said. “I hate to feel like that but, if you look at it, it’s pretty black and white.”Olson said craft companies benefit from any type of retail sale.“If we sell it to medical patients or not, it’s a matter of, ‘Are we collecting the proper taxes?’ That’s all it is,” he said.State revenue from cannabis taxes, licensing costs and other fees goes into the Cannabis Regulation Fund, which is used to fund a host of programs, including cannabis offense expungement, the general revenue fund, and the R3 campaign aiming to uplift disinvested communities.For fiscal year 2024, nearly $256 million was paid out from Cannabis Regulation Fund for related initiatives, which includes almost $89 million transferred to the state’s general revenue fund and more than $20 million distributed to local governments, according to the Illinois Department of Revenue.Medical access still limitedThe state’s 55 medical dispensaries that predate the 2020 legalization law, mostly owned by publicly traded multistate operators that had been operating in Illinois since 2014 under the state’s medical marijuana program, were automatically granted a right to licenses to sell recreationally in January 2020. That gave them a dual-purpose license that no new entrants into the market can receive under current law.Since expanding their clientele in 2020, Illinois dispensaries have sold more than $6 billion worth of cannabis products through recreational transactions alone.Nearly two-thirds of dispensaries licensed to sell to medical patients are in the northeast counties of Cook, DuPage, Kane, Lake and Will. Dual-purpose dispensaries only represent about 20 percent of the state’s dispensaries.While the state began offering recreational dispensary licenses since the adult-use legalization law passed, it has not granted a new medical dispensary license since 2018. That has allowed the established players to continue to corner the market on the state’s nearly 150,000 medical marijuana patients.But social equity licensees and advocates say there are more ways to level the playing field, including expanding access to medical sales.Johnson, who became the state’s top cannabis regulator in late 2022, expressed hope for movement during the fall veto session on House Bill 2911, which would expand medical access to all Illinois dispensaries.“We would like every single dispensary in Illinois to be able to serve medical patients,” Johnson said. “It’s something that medical patients have been asking for, for years.”Johnson said the bill would benefit patients and small businesses.“It’s something we desperately want to happen as a state system, because we want to make sure that medical patients are able to easily access what they need,” she said. “We also think it’s good for our social equity dispensaries, as they’re opening, to be able to serve medical patients.”Rep. Bob Morgan, D-Deerfield, who was the first statewide project coordinator for Illinois’ medical cannabis program prior to joining the legislature, wrote in an email to Capitol News Illinois that the state needs to be doing more for its patients.“Illinois is failing the state’s 150,000 medical cannabis patients with debilitating conditions. Too many are still denied the patient protections they deserve, including access to their medicine,” Morgan wrote, adding he would continue to work with stakeholders on further legislation.Capitol News Illinois is a nonprofit, nonpartisan news service covering state government. It is distributed to hundreds of newspapers, radio and TV stations statewide. It is funded primarily by the Illinois Press Foundation and the Robert R. McCormick Foundation, along with major contributions from the Illinois Broadcasters Foundation and Southern Illinois Editorial Association.

[ad_2]

Source link

-

Politics2 years ago

Politics2 years agoPrenzler ‘reconsidered’ campaign donors, accepts vendor funds

-

Board Bills2 years ago

2024-2025 Board Bill 80 — Prohibiting Street Takeovers

-

Board Bills3 years ago

Board Bills3 years ago2022-2023 Board Bill 168 — City’s Capital Fund

-

Business3 years ago

Business3 years agoFields Foods to open new grocery in Pagedale in March

-

Business3 years ago

Business3 years agoWe Live Here Auténtico! | The Hispanic Chamber | Community and Connection Central

-

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment2 years agoOK, That New Cardinals/Nelly City Connect Collab Is Kind of Great

-

Entertainment3 years ago

Entertainment3 years agoSt.Louis Man Sounds Just Like Whitley Hewsten, Plans on Performing At The Shayfitz Arena.

-

Local News3 years ago

Local News3 years agoFox 2 Reporter Tim Ezell Reveals He Has Parkinson’s Disease | St. Louis Metro News | St. Louis